The elephant in the room

Although tense and uncomfortable, internal and external conversations about racism are necessary for social change

Instead of ignoring it, people in privileged positions can try to learn of ways they can combat hate in everyday situations.

The college town of Charlottesville, VA witnessed a landmark event that marked a new page in the ongoing conversation on race relations in the country.

It was the location of the Unite the Right rally that took place, Aug. 11-12. The rally’s original purpose was to protest the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee, a confederate general, but white supremacists and Neo-Nazis joined the rally to preach their own controversial beliefs. A counter-protest to the rally quickly formed. The main counter-protests were peaceful until a man drove his car into a group of counter-protesters killing Heather Heyer.

“It took a white woman dying for people to realize that something is wrong with race relations in the country.” Sophana Holdegraver, student of color, said.

This blatant display of hatred towards people of color and of the Jewish faith incited powerful emotions, both from those who were being marginalized by this behavior and from those who simply observed what was being said and done in their own country.

The reaction about the violence towards counter-protesters intensified when President Donald Trump made a statement about violence taking place on “both sides,” referring to the white supremacist side and the counter-protester side of the weekend’s events and even mentioning that the white supremacist side had “fine people” on it.

Democrats and Republicans alike were outraged at the fact that Trump did not immediately condemn the message of hate that the white supremacists preached.

If Derek Black, a former white nationalist and son of a former Ku Klux Klan Grand Wizard, can realize the fault in the actions and beliefs he grew up with and later condemn those beliefs, then anyone can.

Individuals closely monitored how their peers responded to the Unite the Right protesters and how they viewed Trump’s response to them.

“I was so surprised about the closeted racism,” Dennis Brock, white student, said. “I dropped so many friends after these things happened and I learned how they really felt about things. I could not be friends with someone who thought that a person of color is worse than a white person or that they are all poor.”

Perhaps the even harder work when dismantling racism is engaging in courageous conversations with people with whom one disagrees. Civil discourse is a vanishing art. Members of Congress from both sides of the aisle realize the importance of speaking out and standing up.

Congress has since introduced a bipartisan resolution that condemns white supremacy, white nationalism, Neo-Nazis and the KKK, as well as calling Heyer’s death a “domestic terrorist attack.” Congress sent the resolution to the president on Sept. 12 with the hope that he signs it.

The prevalence of these events has had people questioning the aspects of racism in society today. But not everyone has to question it; they already have the answers they need.

“Whenever my sister Venie and I go to the outlet mall and we go into Kate Spade or Louis Vuitton, the workers will follow us around a little more,” Holdegraver said. “And then when I come up to the cash register and buy that thing, the looks on their faces are shocked because I can afford it or I’m not stealing it.”

The distrustful eye of a retail employee can be so intimidating that it’s not even worth making an intended purchase.

“I was going to purchase a belt and some pants, and the man working at the store followed me around the entire time,” Ayrianna Dixon, student of color, said. From the moment I walked in, I noticed. He would peek through clothing racks. Once I noticed, I put the stuff back and left.”

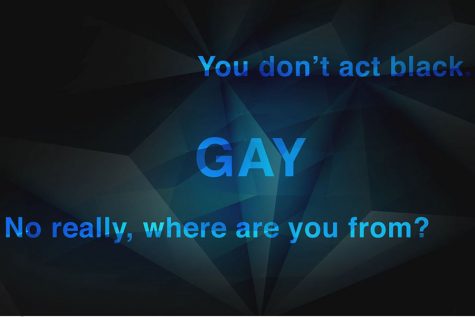

The experience of presumed criminality that Holdegraver and Dixon share is an example of a microaggression.

The journal “Racial Microaggressions in Everyday Life,” published through the American Psychological Association defines Racial microaggressions as “Brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward people of color.”

The journal sums up the concept of microaggressions well: “Perpetrators of microaggressions are often unaware that they engage in such communications when they interact with racial/ethnic minorities.”

While microaggressions are usually unintentional, impact tends to matter more than intent. A study published in the journal “Child Development” showed that racial identity and self esteem go hand in hand for black adolescents. A lower sense of pride in racial identity can hinder self esteem in black youth.

Microaggressions are harsh reminders to people of color of how society views them that can affect how people of color view themselves.

They have been linked to increased depression, anxiety and stress in those who are targeted by them. Microaggressions make targeted people feel like they do not belong in a given environment or like they are abnormal in some way .

“It makes you think about your race more often than others usually do,” Keylan Kirby, student of color, said. “Personally, I have mostly experienced racism online, and I have been called the N word a few times.”

Without speaking up about microaggressions, these actions can become normalized and habitual.

Data shows that microaggressions and implicit biases can have tangible impacts as well. Some examples include:

- Doctors being more likely to recommend helpful cures to diseases to white patients than black patients

- Realtors showing more apartments and houses to white clients than black ones

- Job resumes with stereotypically white names being called back more often than resumes with stereotypically black names

Perceived notions about marginalized groups lead to prejudices about them, prejudiced views lead to habitual racism and habitual racism leads to hate and discrimination. When prejudiced views manifest into hateful views, events like those in Charlottesville can happen.

“I was devastated, honestly, because we’ve come so far in the past several years, in terms of equality,” Smith said. Not only race-wise, but in terms of sexual orientation as well. And this is just a huge step backwards, and it was really disappointing to me, also, because we’re seeing a ton of this.

The United States Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage nationwide on June 26, 2015. Although other countries like the Netherlands had legalized same-sex marriages as early as 2000, this was a monumental step for the U.S., as it brought attention to the fundamental rights of those in marginalized groups.

Images of hatred for other marginalized minority groups, whether racial or religious, are a reminder of the long path to equality for all.

The journey to a less prejudiced society is a long one. The first step anyone can take is to recognize their own problematic behaviors. However, it’s not enough to simply acknowledge the behaviors. What matters is the work that is done to learn about and correct the behaviors as well as identifying the behaviors in others and engaging them in hard conversations about these beliefs.

The Implicit Association Test is a quick way to begin the process of self-assessment of prejudiced behaviors.

The IAT measures attitudes that people have towards groups of people through implied associations. The main idea of the IAT is that people will have a quicker response to implied messages they have internalized, whether intentionally or unintentionally.

Though the results of this test do not determine someone’s prejudice, they can predict the behavior that someone can have around another person.

Once the privilege and prejudice inside is recognized, the next step is to be educated on how these behaviors can be corrected and how to be an effective advocate for change.

“I work really hard to be an ally, but I also work really hard not to be a savior,” Jennifer Strauser, associate principal, said. “I’m learning in the most recent years that it’s more about me asking people who are oppressed what they need instead of me thinking I know what they need.”

After self-assessing and learning about what actions need to be fixed, the knowledge needs to be spread to peers.

“It’s not as hard as people think it is just to be like ‘Oh dang! Someone’s saying this!”’ Brock said. “You have to just be vocal in every single situation and tell people when they are wrong. You cannot try to be some kind of mediator between these kind of issues.”

Using privilege and self-awareness to stand with those advocating for racial equity can continue to spread awareness.

“Protesting is one way that privileged people can condemn racist acts,” Claire Baechle, white student, said. “We [white people] need to stand up if people of other races are getting worse treatment, for example, with police brutality because we have that kind of privilege.”

Encouraging students of all races to have a voice in the classroom and promoting diversity in all forms of expression are important aspects of inclusion, which is one key way that teachers and students can work together to eradicate racism and racial prejudice at school.

“It’s crucial to foster a positive classroom atmosphere where everybody’s valued,” Robyn Stellhorn, Staff Equity Team member, said. “Promoting various artists from whatever cultures they happen to be. Writers, poets, just all kinds of success stories exist. That sort of recognition is important.”

Teaching the youth about combating racism at a young age can give them the tools to fight for change in the future.

“As a mom of two kids, I can be an agent of change,” Kristy Raymond, Staff Equity Team member, said. “I am part of a movement in St. Louis called “We Stories”. Each month, a different book about race or religion or another minority is highlighted and we are given target questions that we can talk to our kids about. I have an open dialogue with my kids about it and that’s where I feel I’m making my change.”

Supporting peers in marginalized groups is another way to combat racism and prejudice on a daily basis.

“You need to have a strong mind and a group of people to follow through with you,” Dixon said, “It’s not something you can do on your own. It’s something that needs to be done with other people to support you and your ideas.”

Just because racism isn’t always directly in front of a public audience doesn’t mean it isn’t happening.

Whether through microaggressions or through more blatant, outspoken acts, acts of racism happen every day. They will continue to happen well into the future unless people in privileged positions use their privilege to advocate for change.

“This is not a ‘both sides’ issue; it’s a one sided issue,” Brock said. “We fought Nazis before. We fought confederates before. This is America’s history.”

Want to take the first steps towards change? Take the Race IAT and let us know how you did.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Eureka High School - MO. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

@mperezEHS_hub

This is Perez's third year on staff where she serves as a reporter for the Hub. One word to describe her: independent. Perez is involved...

Miller is a reporter for the EHS-hub. She has been on staff since the first semester of her senior year, returning after taking Journalism, Writing, and...

This is Newton's fourth year on staff where she serves as the managing editor on the 2018 Eurekana staff. One word to describe her: eccentric. Conversation...