Up in the air

A look at increased graduation requirements and increased pressure

Today, graduates need more total credits, more core credits and less electives than graduates in 1993 did.

The Class of 2017 will be walking across the Chaifetz Arena stage in their purple caps and gowns to receive their diplomas, May 24. For the last four years, they have balanced their schedules with additional commitments inside and outside of school. To balance all of these activities, choices had to be made.

Those choices could take a toll. School is a significant source of stress for 83 percent of students, according to the American Psychological Association.

The National Institute of Mental Health reports that about one in four students have an anxiety disorder.

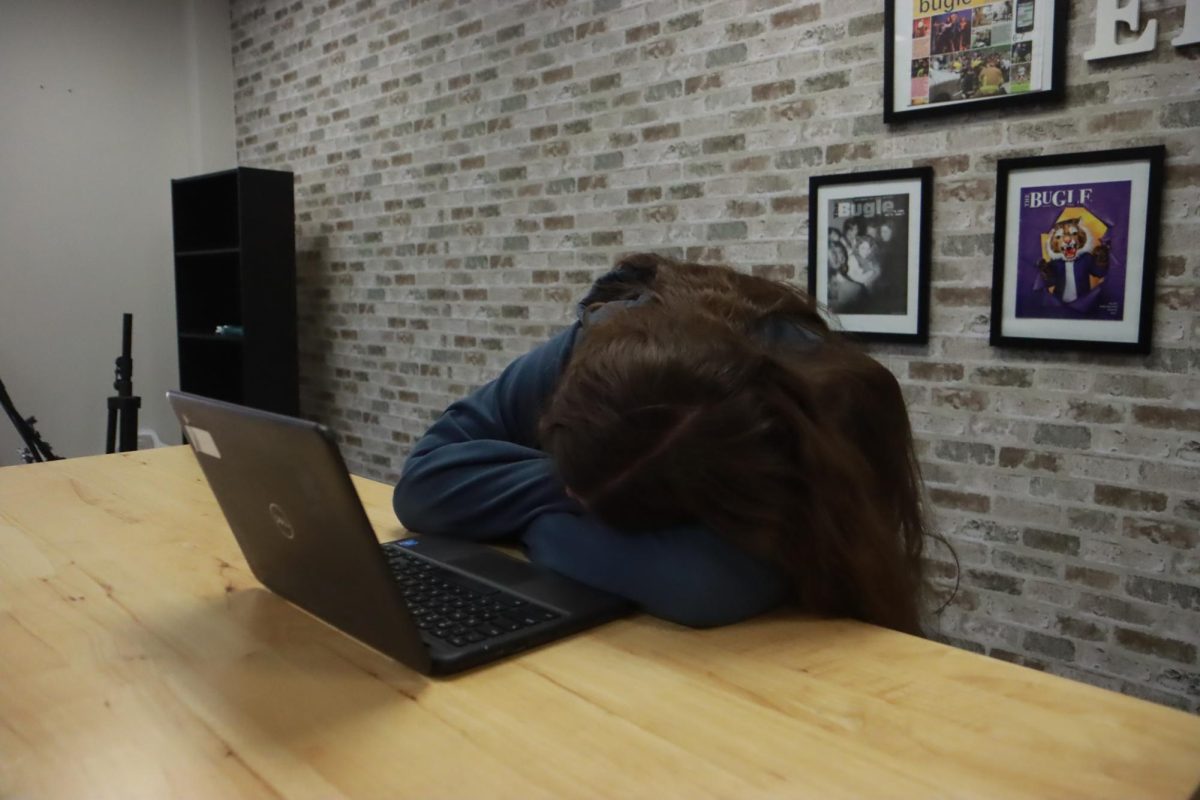

So the fact that the Sleep Foundation published that teenagers rarely get the eight to 10 hours of sleep they need should come as no surprise.

“When it comes to school, you just do what you have to do,” Madison Flower (11) said. “Sometimes I get as little as five or six hours of sleep because I stay up as long as it takes to get everything done, especially for AP Gov., Algebra 3 and Human Anatomy. I have a part-time job at Crestview Middle School, and I get home from that around 8 p.m. So I don’t get to start my homework until then.”

As a first step in addressing stress with the school community, the administration held the first Health and Wellness Day, Nov. 21. In that story, Charles Crouther, head principal, commented that he believed the support systems that students need are already in place that students need.

“I do not think it is a greater challenge for kids to find balance,” Crouther said. “The students in my opinion are more involved now, but they have a support group at home and with friends, coaches and teachers that help them balance it out and schedule the activities so they can get it all in.”

The data about anxiety and stress indicate otherwise, and changes to state graduation requirements added more classes to students’ course loads.

INCREASE IN REQUIREMENTS

The Missouri State Board of Education shifted the state graduation requirements in 2005, effective beginning with the class of 2010.

The State Board of Education establishes minimum graduation requirements that are designed to ensure that graduates have taken courses in several different subject areas and mastered essential knowledge, skills, and competencies.

The average first-time parent was close to 25 in 2000 and would have graduated from high school in 1993. Their children, current sophomores and juniors, now participate in a high school environment that expects more out of their students than when their parents attended the same institutions.

In Missouri, 24 credits are currently needed to graduate, but in 1993, high schoolers needed 22 credits to get their diploma. This shift had far-reaching implications. Districts across the state adjust schedules, so students could find room to take study halls and electives.

RSD high schools shifted from a six-period standard day to a seven-period hybrid block schedule in 2006 to accommodate the increased number of credits

Not only has the amount of credits needed changed over time but the type of credits have also.

In 1993, high schoolers needed two math, social studies and science credits to graduate. Now, the number has been raised to three credits for each of those classes. Also, the amount of language arts credits required increased from three to four.

This increased requirements came with an increase in difficulty. Current high school students now take classes in subjects their parents took in college.

“Some of the classes students take in high school, we didn’t take until college,” Leah Tomschin, parent, said in a phone interview. “I know my daughter Chloe’s algebra textbook is similar to the textbook I used in college.”

In addition to earning more core credits than in the past, graduates also need to earn a half personal finance credit and a half health education credit to graduate. The state added those requirements at a time when people were falling victim to credit card debt and America’s obesity problem could no longer be ignored.

High school education is no longer basic.

The risks of identity theft and the challenging concepts of checking and credit are some of the things that inspired the required personal finance credit. Other topics in the course curriculum include career exploration, investments, insurance and taxes. Knowledge on these topics is needed beyond high school.

“I remember my dad telling me he never took a personal finance class,” Carly McKee (12) said. “That class was really, really boring but I’m glad I took it and I’m glad that the class is a requirement.”

In health education classes, students learn valuable information that is needed to maintain a healthy mental and physical life. The required course teaches various topics like how certain systems in the body work, how to determine an unhealthy relationship, how to read food labels and how to maintain a well-balanced diet. Health education also informs students about peer pressure and promotes smart decision-making.

The ability to maintain both financial stability and a healthy life are skills needed in adulthood. Making these credits required will ensure that high school students get a head start on utilizing these skills.

“I graduated in 1976. When I went to high school, we had fewer courses available,” Patti Fleer, orchestra, said. “Things like choir, orchestra, band, art and photography weren’t available. We also didn’t have sports for girls like we have now. I remember playing dodgeball every day. Not fun, encouraging or educational.”

A.C.T. AND POST-SECONDARY EDUCATION

Colleges also play a large role in what credits are needed. Different universities have specific requirements for the amount of high school credits incoming freshman need.

For example, the University of Missouri-Columbia requires four math credits as well as two credits in the same foreign language for incoming freshman.

Another requirement for admission to schools in the University of Missouri system is an A.C.T. or S.A.T. test score. Most four-year colleges and universities nationwide require at least one score from either test.

The Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education mandated that all juniors take the A.C.T. at the same time and under standardized administration conditions beginning with the 2014-2015 school year. Now college hopefuls have a chance to fulfill the requirement at no cost. This year, EHS juniors took the exam, April 19.

“Back when I went to high school, everyone took the A.C.T. once,” Diane Thomas, parent, said. “You didn’t care what you got. You just took it. Here, it’s such a big deal because everyone wants to get to a 30 or more.”

The average A.C.T. score in Missouri is a 21.6, but colleges often ask for higher scores. For example, at Missouri State University, the average A.C.T. ranges from 21 to 26 on a 36-point scale, but at the University of Missouri-Columbia, the average A.C.T. score range is 24 to 29.

The idea is strong curricula help students perform better on these nationally-normed tests.

These college demands tend to influence the course load for today’s high schoolers. To keep up with the demands colleges require, Missouri shifted the state requirements to align those state requirements closely with what colleges expect from applicants.

“I tried to be really smart to make sure I get all the credits I needed so that I could still have the high school experience and at the same time do everything that I want for my career,” Destinie Jones (12) said. Jones wants to be a veterinarian, an intensive program at Maryville, the school she is attending.

Students who know what they want to do and where they want to go will consider sacrificing free time and a smaller workload for the classes they need to prepare themselves for college and their future careers.

“I feel like the pressure to do well and achieve better grades to get into college is stronger than when I was a kid,” Michelle Eickel, parent, said. “I had way less homework.”

DEGREE OF DIFFICULTY

A study conducted by the National Assessment of Educational Progress shows that the homework load of the average 17-year-old high schooler has remained at a stable amount from 1984 to 2012 while the difficulty of the homework has increased. In 2009, 59 percent of graduates were in accelerated classes.

For instance, the number of high school graduates who completed Algebra 2 and Trigonometry increased by 22 percent from 1990 to 2009, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

“I want to get into a really nice college,” Caroline Kneedler (11) said. “That’s my motivation to keep going and not give up.”

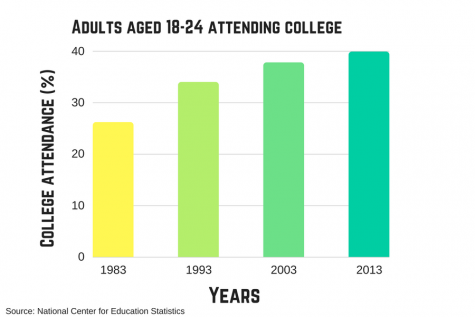

The motivation to obtain more than just a high school diploma is greater than it used to be. In fact, the percentage of 18 to 24 year olds attending college rose from 34 percent in 1993 to 40 percent in 2014, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Though slightly stabilizing, the amount of young adults attending college is also on the rise.

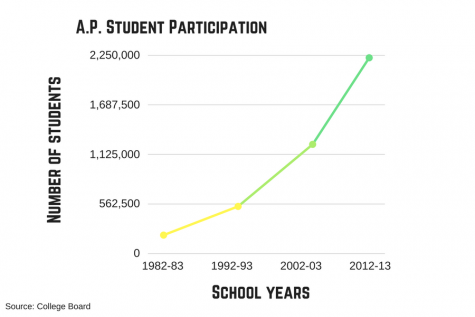

The increase in motivation to attend college has inspired enrollment in advanced placement classes. Passing an AP exam in the spring can reward test-takers with college credit.

“I take AP classes so I can get ahead when I go to college,” Kate Daniels (12) said. “It’s nice because I’ll already have that knowledge.”

Although they are difficult, AP and weighted grade classes are a way for students to be better prepared for college-level courses.

Angelena McMurray (11) took her first two AP courses this year.

“I have to make time, at least two hours in my day to study,” McMurray said. “Often times I come to school around 7:00 a.m., and I study in the library. When I get home, I take an hour off and then I study for another hour.”

The knowledge isn’t the only benefit. A $93-fee for one AP exam could save a student (or their family) three-credits cost at the college of their choosing. That’s $765.43 a credit or $2,296.29 for three-credit hours at Mizzou.

AP enrollment rose from 424,000 in the 1992-93 school year to 2.6 million in the 2015-16 school year.

The number of students in the AP program has increased dramatically between when past generations went to high school to present day.

21ST CENTURY SKILLS

This increase indicates that more students are taking the initiative to do what they need to in order to make themselves competitive for college and life after. For example, classes are focusing more on communication.

“We don’t spend nearly as much time on verb drills or worksheets because we focus more on helping our kids learn how to communicate with others whether it’s through talking directly to people, reading or writing,” Christie Staszcuk, German, said. “This will not only help kids in foreign language classes but in all other classes and in being a good employee later on.”

Current curricular requirements have shifted emphasis, too, away from being solely knowledge based to mastering skills.

“For the classes I teach, the curriculum has become more skills-based,” Gary Baumstark, Language Arts, said. “Instead of taking multiple choice tests over the material in ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’, for example, we will work on reading and writing skills throughout “To Kill a Mockingbird” and then students will read another text and apply those same skills.

The importance of basic life skills, the growing desire to attend college and the increased participation in accelerated classes likely resulted in the decision to shift the Missouri graduation requirements. Other states saw an increase in required credit for core classes around the same time period, which went into effect between 2012 and 2014.

People who graduate this year move forward with more tools to succeed than past generations because of the increased demand to grow from their core studies.

“I now know how to study and what does and doesn’t work for me,” Natalie Budd (12) said. “When I go to college, I know I can study effectively.”

Skills picked up through taking challenging classes can not only be used in college but also in the professional world.

“I’ve seen there’s a bigger emphasis on writing,” Thomas said. “That’s important because as kids are getting more used to texting, which doesn’t require punctuation and full sentences. In the real world, you need to be able to write full sentences, letters and reports.”

The preparation for the world beyond the walls of the classroom could stretch young brains too thin. With taking difficult required classes and fitting in extracurriculars, there is an added pressure in students’ lives.

“I tend to be a perfectionist,” Flower said. “If I miss even a point on a test, I’ll get stressed out about it because I want to be perfect.”

The pressure to be an ambitious, high-achieving student has negative consequences.

CONCLUSION

A study conducted by the American Psychological Association revealed that 31 percent of teens feel overwhelmed and 30 percent feel depressed or sad because of stress.

The push towards college is greater than it was before, as undergraduate enrollment is expected to increase 14 percent from 2014-2025. High schools have to fulfill the needs for students who hope to join that statistic.

The tools needed to produce productive, versatile individuals through education are in place. These tools were greatly enhanced thanks to a shift in graduation requirements.

However, current requirements emphasize the importance of being prepared for the future, but–because more work is involved for students today than there was for their parents–stress could play a bigger role for current high schoolers than it did for theses students’ parents when they were in high school.

If the aim of the current school system is to make sure the academic aspect of students’ lives provides all the tools needed to produce a well-rounded citizen that will find success in their adulthood and careers, perhaps those tools need to be expanded to include strategies to manage stress.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Eureka High School - MO. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

@mperezEHS_hub

This is Perez's third year on staff where she serves as a reporter for the Hub. One word to describe her: independent. Perez is involved...

This is Kelsey's first year on staff. You can follow her on twitter @kroloEHS_hub. Her hobbies include dancing, and listening to music. Outside of school...